Home » 2023 (Page 3)

Yearly Archives: 2023

General Westmoreland and the Vietnam War Strategy

Returning to John Mason Glen’s opinion piece in the New York Times (“Was America Duped at Khe Sanh?”) We must also set the record straight about General Westmoreland and the strategy in Vietnam War. Again Mr. Glen displays his lack of historical perspective by attributing the strategy of attrition in the Vietnam War to General Westmoreland’s analysis of the battle of the Ira Drang Valley. (The basis of the book and movie We Were Soldiers Once, Young and Brave.)

Glen correctly paints General Westmoreland as the perfect image of a soldier—World War II leader, Airborne Infantry leader, former Superintendent of West Point—with a very stiff soldierly look. Westy, as he was called by cadets at West Point and soldiers in the field in Vietnam, was all that Glen describes. One must also remember at this point in history the Airborne Mafia, as it was called, ruled the Army. There was admiration for the Airborne coming out of World War II. President Kennedy was enamored with the Special Forces (Green Berets) all of whom were airborne qualified. Glen attributes Westmoreland’s strategy to this background and does not attribute the country’s experience and successes in other wars to the strategy in Vietnam.

When Westy was superintendent at West Point I was a cadet there studying military tactics and history. Much of our studies revealed that the US military strategy grew out of Grant’s defeat of Lee in the Civil War. The battles of the Wilderness in late 1864 and 1865 were battles of attrition. The North had the wherewithal in terms of men and equipment to fight a war of attrition against the South. This strategy succeeded. The lesson learned was that attrition warfare was a way to win.

The world wars in Europe and Asia were also wars of attrition where superior resources were able to win the day, over time. When one couples the US military experience of success through attrition warfare with Robert McNamara’s “bean counting” revolution in the Pentagon one can understand how body count became the measure of success for the war in Vietnam. If more bad guys were killed in an engagement than good guys then the good guys “won”. This became the approach in Vietnam.

Given this view that attrition / body count would cause the enemy to stop fighting one can clearly understand the desire for a set piece firepower intensive battle to crush the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). Khe Sanh offered this opportunity. The hope was that the NVA would go for the bait that was the Khe Sanh Combat Base and provide a large number of targets to be attacked by superior fire power and destroyed. For this strategy to succeed the bait could not be compromised by the NVA learning of the plan. The close-holding of the intelligence that the NVA was going to attack Khe Sanh lead to my advisory team in Khe Sanh village being “expendable”. We were part of the bait and could not be allowed to leak to our Vietnamese counterparts what was coming for fear that they in turn would leak it to the NVA. The solution was to just not tell us what was about to occur.

Some of the readers of Expendable Warriors have commented on how critical I deal with General Westmoreland. One former Chief of Staff of the Army refused to endorse the book because of this perspective. I must admit that the after taste of being “expendable” may have colored my perspective. However, I have learned the bigger lesson—strategic leaders must make strategic decisions based upon the bigger picture. In this regard the small advisory team and mixed force of Vietnamese, Bru Montagnards and Marines may have truly been expendable. Though we will probably never admit it and obviously did not fight like we were.

The soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines of multiple countries did not lose the war in Vietnam the politicians and strategists did. In April/May of 1968 the strategy had succeeded. The NVA and Viet Cong had been defeated by all body count measures, but the political will to win was gone. The concept of political will had not been considered by the strategists of the day. It was not until Colonel Harry Summers published his book On Strategy; a Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War that Clausewitz’s dictums on political will were brought again into consideration by American strategic thinkers. Colonel Summers was part of the US Vietnam negotiating team and his discussion with a North Vietnamese counterpart is often quoted. He told his counterpart: “we won every battle.” To which the North Vietnamese officer replied: “But you lost the war.”

If one reads my writings on conflict termination, he will see Colonel Summers’ views used as a basis for defining what it means to win. Body count is also dismissed as the failed measure of success that it is. In discussing Ukraine body count and tank count are seeping back into the analysis of the situation. One should not be overly impressed by the numbers.

The battle is won and the war is lost

As we wrap up this year’s relook at Khe Sanh those who wonder why I am devoting so much time to this effort every year will hopefully come to realize that there is much to be learned about winning conflicts and what it takes to win. I have been asked to relook the Ukraine, which I will do, but I ask my readers to think about winning and what Khe Sanh has taught us.

On the 1st of April 1968 the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) launched Operation Pegasus. Many newly interested authors focus on the battle for the old French fort. What they don’t realize is that just as the operation was beginning the war was being officially lost.

As the senior advisor in Khe Sanh before the beginning of the “agony of Khe Sanh” on 21 January 1968 I was two months later seconded to the 1st Cavalry Division to assist in the planning for Operation Pegasus. (For a complete discussion of the siege of Khe Sanh see: www. Expendablewarriors.com or my recent postings here.)

It was strange to fly over what had once been the area along route 9 and see rice paddies where there had never been paddies before. In actuality what I was seeing was bomb craters that were filled with rain water. (I flew into Khe Sanh with Major General John Tolson (commander of the 1st Cavalry Division) several times,

During the planning process units from the 1st Cav, the 101st Airborne Division and the 3rd Marines were conducting operations along the DMZ as a diversion to the relief operation. The engineers were busy building a short runway and underground bunkers for the command and control of Operation Pegasus near Calu. The new facility was to be named LZ Stud.

For Operation Pegasus the 1st Cav had an extensive set of capabilities

- The 1st Cavalry Division with its 400+ helicopters

- A Marine BDE with augmenting engineers and artillery

- An Army of Vietnam (ARVN) airborne brigade

- 26th Marine Regiment +–the whole force defending the Combat Base (5000 strong)

- Massive air support

This was the equivalent of a small Corps.

The attack began the morning of the April 1st with the Marine Brigade attacking along route 9. Its mission was to open Route 9 from LZ Stud to the combat base. This required the repair of numerous road by passes that had been destroyed by the NVA and neglected for more than a year. The air assault was delayed until 1 PM due to fog in the Khe Sanh area. The initial air assault was into areas where the vegetation had been flattened by use a bomb called a Daisy Cutter (a 20,000 pound bomb that was dropped from a C130 aircraft and detonated when the long pipe that was its detonator struck the ground—thus creating standoff and blowing things down without creating a crater). The Infantry and engineers followed to secure the area and move the blowdown so that howitzers, crews and ammunition could be lifted in. As a result, a firebase was created.

With fire support for support of the infantry and to support the next hop forward closer to Khe Sanh the next unit could be inserted and the leap frog towards the combat base and the enemy could continue.

It was on this day 1 April 1968 when the war was lost. Major Paul Schwartz, the division plans officer and a previous contact from my days in Sandhoffen, Germany) and I had to brief General Tolson on the proposed concept for the Division’s next mission—clearing the NVA out of the A Shau Valley (about 40-50 kilometers south of Khe Sanh). There were 4 people present at the briefing—General Tolson, his Chief of Staff, Major Schwartz and myself. We proposed attacking through Khe Sanh to the Vietnam-Laos border. Going into Laos, cleaning up the Ho Chi Minh Trail and then turning south to enter the A Shau Valley from the west—not the traditional route which was from the east. There were 90 days of supplies at Khe Sanh to draw upon and thus not have to back haul them. The forces were available, and most importantly such an approach would have caught the NVA by surprise and had war winning effects.

After about 4 minutes of briefing General Tolson said: “Obviously you didn’t hear the President last night! What you are proposing is politically impossible.” Lyndon Johnson had just announced a partial bombing halt in an effort to enter negotiations with North Vietnam.

About 5-6 days after the initial assault began a link up had occurred at the combat base with reposibility for its defense being transferred to a brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division, the Marines had attacked north-west out of the combat base. Also the ARVN Airborne Brigade had been inserted into the battle to the west of the combat base and a brigade of the 1st Cav had secured the old Lang Vei Special Forces Camp. The relief operation was ending.

3 years later the US was to support ARVN forces in Lam Son 719A which was an attack into Laos where the ARVN got clobbered. The NVA had used the 3 years to recover. A year or so later President Nixon was to start the B-52 bombing missions over Hanoi and Haiphong. These would result in a peace agreement.

President Johnson’s bombing halt decision was when the US decided to not try and win the war on the battlefield—just as the NVA were on the throes of collapse. The war was winnable after the eventual Khe Sanh and Tet victories, butduring almost 3 months the political climate in the US had so turned against the war there was no political will to try and win on the battlefield.

In coming articles, we will talk about the bigger lessons learned from Khe Sanh and other conflicts. It is my hope that someday some ”wanna be strategists” will read these articles and learn something from them about fighting and winning battles and wars.

The noose tightens

Recently, when reading my VFW magazine I encountered an article entitled Tanks in the Wire”. It was a brief, but still not accurate, synopsis of the battle of Lang Vei Special Forces camp on 7 and 8 February 1968—55 years ago. (I would commend David Stockwell’s two books on the battle. First came Tanks in the Wire and just recently The Route 9 Problem) I was underground in my bunker at the Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB) but listened to much of the battle on the radio and the next morning was part of the planning for the relief effort for the beleaguered forces at Lang Vei.

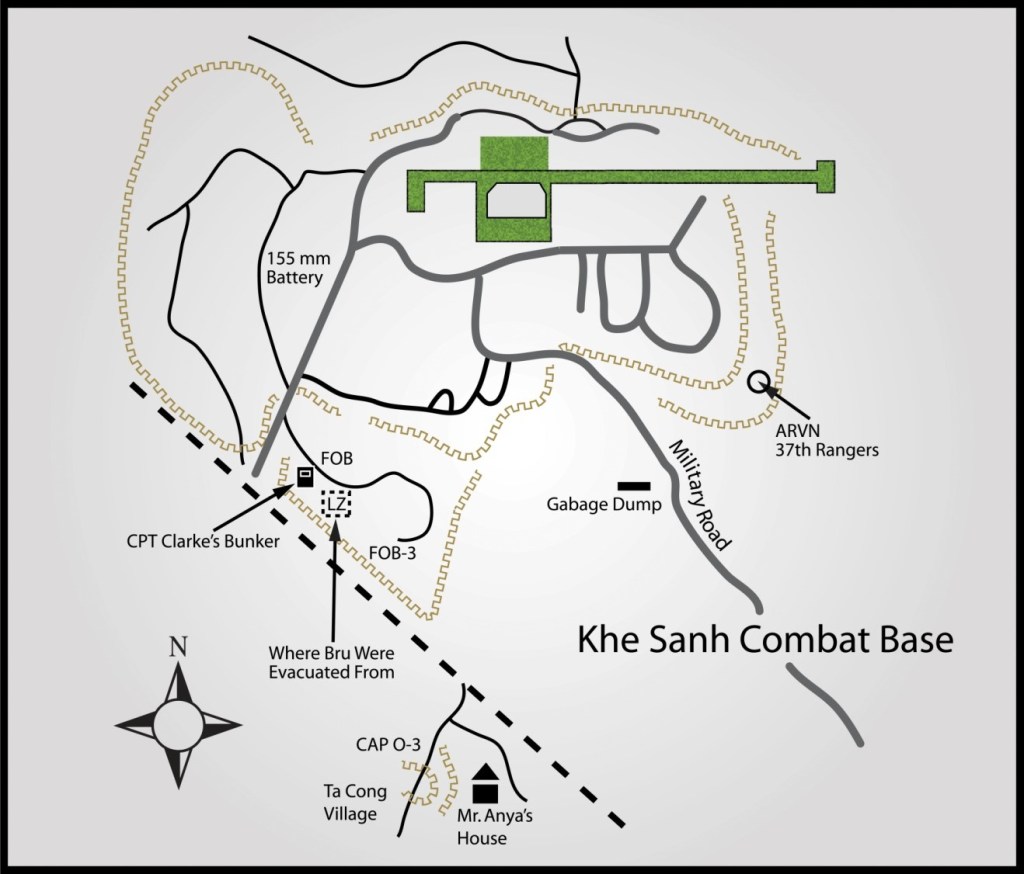

To put the battle in perspective it actually started at the end of January when the 33rd Royal Laotian Battalion was overrun by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) in Laos using tanks. The Surveillance and Observation Group (SOG) Special Forces at Forward Operating Base 3, which was an appendage to the KSCB and where we had the local Vietnamese government in exile, had a close connection to the Laotians.

When the Laotians reported that they were overrun by tanks nobody believed them. The 33rd Battalion fled Laos and settled at Lang Vei in a camp near the Special Forces Camp. They were reinforced by Special Forces elements from Hue Phu Bai lead by LTC Schungel. So now there were two Special Forces camps at Lang Vei—the old camp with Laotians and Special Forces in it and the new camp with A 101 and its Vietnamese Civilian Irregular Defense Forces (CIDG). CPT Frank Willoughby, the commander of A 101 Special Forces detachment at Lang Vei requested anti-tank mines but his request was denied because the report of tanks being used was not believed by higher headquarters. The Special Forces did scrounge some Light Anti-Tank Weapons (LAWs).

The scene is now set with two camps near the Bru village of Lang Vei and track sound being heard on several evenings before the attacks. On the evening of 8 February the new camp was hit with artillery and mortar fire followed by an infantry attack led by PT 76 light amphibious tanks. The forces fought back and called artillery from the KSCB on the attacking NVA. Some of the LAWs failed to operate correctly and many of those that did were ineffective. Eventually, the defenders of the new camp either secluded themselves in the deep underground command bunker or fled to the old camp. The fight continued all night long. CPT Willoughby requested reinforcement by the Marines from KSCB, but was turned down twice!

Communications from the command bunker became difficult with the antennas knocked down but the single side band radio with its buried antennae continued to allow communications to the outside. At the is point there was a PT 76 tank on top of the command bunker and the NVA were throwing tear gas down into the bunker. CPT Willoughby and his crew continued to communicate.

Forces from the old camp, supported by artillery and air strikes made up to five attempts to reach the bunker with no success. The 7 weak from wounds and dehydration survivors in the bunker made their plans to escape. CPT Willoughby told the aircraft overhead to make 3 hot strafing runs over the camp and then make runs without firing. During the “dry” runs the survivors would make a dash to the old camp. Actually, it was to be more of a limp. The survivors met little opposition and with the help of a brave Vietnamese Lieutenant who drove a jeep to pick them up made it to the old camp.

The final saga of the battle was the evacuation. There are several versions the fight for helicopters, but COL Ladd, the 5th Special Forces Commander in Danang was forced to go to General Westmoreland who was in a meeting with LTG Cushman (the Corps Commander) and could not be disturbed. COL Ladd turned to GEN Abrams who had established a MACV forward command in the northern part of the country. GEN Abrams ordered the Marines to release the helicopters to rescue the survivors of the battle. The relief operation was planned by the Special Forces at FOB 3 and lead by Major George Quomo. After the reluctance of the Marine CH 46 helicopter pilots to land at the old camp the Americans and the wounded along with the Laotian Battalion leadership were evacuated by air to KSCB and then once medically treated were taken to Danang. The individual soldiers and the Bru and Laotian civilians were left to fend for themselves. They walked the distance to the combat base where they were disarmed and turned away. (This was to create a political incident between the Laotian government and MACV.) I radioed Quang Tri thru my radio relay that the 1500 or so mixed group was on its way. The advisory team in Quang Tri prepared to house and care for these stragglers. The Laotians were evacuated through Saigon back to Laos.

Route 9 was now not impeded—the Lang Vei and District Headquarters impediments had now been removed. The route to the KSCB was now open and the noose had been tightened.

Modern tanks for Ukraine

Modern Tanks for the Ukraine[i]

In recent days there has been significant dialogue within NATO about providing Ukraine with modern tanks. The British have promised. a company’s worth of Challenger II tanks. Other NATO countries were willing to provide German made Leopard II tanks. But to do this they needed German approval.

Bringing an end to a internal NATO row, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz finally confirmed that Germany will send its own German-made Leopard 2 tanks to Ukraine and allow other NATO allies to deliver some of theirs.

Scholz even teased further deliveries of air defense systems, heavy artillery and multiple rocket launchers and said Germany ‘intends to expand what we have delivered’, a major U-turn on the chancellor’s previous reluctance.

President Biden in turn promised that the US would provide 14 M-1 Abrams tanks. (There was no clarification of which version of the M-1 would be provided. To make it simple the initial M-1 had a 105 mm rifled gun, the M-1A1 that went to the Gulf War had a 120 mm smooth bore cannon, the M1A2 that the Saudis bought had an improved target acquisition system and other improvements. The latest version M1A2Sep5 has many modernized features.) (It should be noted that the Leopard II and the M-1 both have a common ancestry. The both evolved from the US German co-development of what was called the MBT—Main Battle Tank. But in the late 1970s the two went their separate ways,) The Leopard II also has a series of newer versions. Again, we don’t know which version that the Ukrainians are getting. One would hope that there is some consultation between the NATO Leopard II providers so that the versions provided are mostly the same for ease in training and maintenance.

The Ukrainians have offered that these modern tanks with night vision capability, improved armor, and superior fire power with greatly improved target acquisition capability will save lives, improve their ability to destroy Russian tanks and maneuver on the battlefield.

The above is true, but there is a big HOWEVER! The fact that the three tank models in question are not interoperable in terms of ammunition, spare parts or maintenance needs is an obvious huge nightmare. Even more nightmarish is the knowledge that it takes to operate and maintain each system. The train up time for operators will be measured in months, not days or weeks. Probably the training will occur at the joint training facility at Grafenwoehr, Germany where both Abrams and Leopard tanks are readily available. But the Germans will probably need translators to teach in German and get the information translated into Ukrainian. The same will most likely be true of the US trainers. (Such training doubles the time it takes to conduct the training. Then all of the operator and maintenance manuals for the two systems must be translated into Ukrainian. The M-1 has a large system for diagnosing maintenance faults, which could take an extensive training period. To get these modern tanks into the battle this coming Spring is going to require US, German and British maintenance crews to accompany them.

It would be a major omission if the fuel consumption rate of the M-1s was not mentioned. The Challenger and Leopards each have diesel burning engines. HOWEVER, the M-1 has a turbine engine (similar to ones found in aircraft.) It gets about 3 gallons to the mile! Fuel resupply will be both a large issue and a vulnerability of the M-1 battalion worth of tanks that the US has said that it would provide.[i]

It would be a huge escalation of the maintenance crews mentioned above wore the uniforms of their respective countries. There are several large defense contractors who have operated training efforts in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere who could probably step up to such a task fairly quickly. They use retired military to perform the training and maintenance missions. Who is going to pay for this?

These practical execution issues are not trivial. But what about the Russian reaction to the perceived escalation? Russia warned that Germany’s decision to send dozens of modern tanks to Ukraine is ‘extremely dangerous’ and will ‘take the conflict to a new level’. It branded the move a ‘blatant provocation’ and warned the new NATO supplies will ‘burn like all the rest’, while one raging propagandist called for the German parliament to be destroyed in a nuclear strike.

The Russian reaction should have been anticipated by the west. Another Russian reaction is the vast mobilization of manpower that is currently going on. The Russians are reportedly giving two million men very rudimentary training. Some in military skills and others in skills to free men up from industry to provide additional members of the military.

So, both sides are making lots of escalatory and working very hard to show a willingness to see their way through an extended war. This suggests that it will be internal political reactions in either NATO or Russia that will force this conflict towards termination.

The announcement of modern tanks for Ukraine has certainly raised hopes and raised the propaganda level. Only time will tell, about their effectiveness on the battlefield. We will follow this issue closely in coming months

[i] Colonel (ret) Bruce B. G. Clarke commanded 2/11th Armored Cavalry squadron when it fielded the M-1 tank (53 tanks) in 1983-4. During that time, he also fired a Leopard II. He commanded the 2d BDE, 1st Infantry Division with two battalions of M-1s (88 tanks) and after retiring was the head of the training team in Saudi Arabia training the Saudis to operate and maintain the M1A2 tank (120 mm gun and improved target detection and other advanced features.).

[ii] The one thing I learned as a commander of units with M-1 tanks was that refueling and fuel locations became critical elements of any tactical plan. I am sure that that is still the case.

False Quiet

Following the fight around the District Headquarters and the artillery strikes and attacks against the Marine hill positions a false calm settled over Huong Hoa District. The calm was characterized with massive reinforcements and defense construction on the Vietnamese / American coalition while the North Vietnamese were consolidating their newly achieved freedom of movement.

The Marines added three infantry battalions to the two that were already manning the Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB). They also brought in the 37th ARVN Ranger battalion. (The Vietnamese leadership wanted to use this battalion to re-seize the district headquarters, but the American leadership, with an attrition strategy and a free fire area at the center of it demurred.)

At FOB 3 fortifications were being built reminiscent of World War I. There was a trench line that extended from the northern edge of the FOB to the southern end and then turned northwards to tie in with the Marine positions. The trench line was characterized with fighting positions facing outward with claymore mines and trip flares in the multiple rows of barbwire–to include concertina wire. Behind the trench line were living bunkers where the defenders slept, ate and other wise survived. After the first contact anywhere near the wire more sandbags were added to the back of the trench line to protect the defenders from the fire from the Marines behind them. (There were no routes through the Marine war so if the FOB 3 defenders had become over run they had no where to retreat to and would have had to retreat through the fire form the Marines to their rear,)

FOB 3 trench line showing several Bru fighters

FOB 3 on the southwestern edge of KSCB

Meanwhile to the west of the combat base in Laos the North Vietnamese were attacking the 33rd Royal Laotian Army battalion. The battalion was over run and fled east into South Vietnam and were received at the Lan Vei Special Forces camp. Actually the Special Forces reinforced their US contingent and reoccupied what had been the old camp. The Laotians reported that they were over run by tanks. No one in the chain of command really believed them. But back at KSCB CPT Clarke was charged with installing and properly recording the installation of an anti-tank minefield where the FOB 3 defenders could cover it with fire.

The noose is about to tighten.

Story of the Village Fight

As written in April 1968

The scene of the action—Khe Sanh village and the District Headquarters in the bottom center of the map

These place names were referred to extensively over the last few articles

The District Headquarters –note the red arrow for the location of the NVA main effort—at the seam between the District Headquarters and the Regional Force Company compound. Also note how tight everything is. From the Pagoda to the wire is less than 10 yards.

Much of what follows will be repetitive of what you have already read. However, it is published here so that you can see what was actually written in April of 1968.

1968 Advisory Team 4 Newsletter

There was a battle fought in Khe Sanh on 21 and 22 January 1968 that very few people know about. Everyone knows of the artillery barrages and the trenches, but one of the big battles took place when at 05:00 hours 21 January 1968 the 66th Regiment, 304th NVA Division launched an attack against the Huong Hoa District Headquarters in Khe Sanh Village (about 4km south of the Khe Sanh Combat Base). The District Headquarters was defended by an understrength Regional Force (RF) Company, elements of 2 (Popular Force) PF platoons and Combined Action Company O (CAC-O) Headquarters and one Combined Action Platoon (CAP) with 10 or more Marines.

The attack was from three directions with the main effort coming from the southwest against the RF Company. The weather was extremely poor with very heavy fog. The initial enemy assault was beaten off by the courageous efforts of the RF Company and by almost constant barrages of Variable Time (VT) fused artillery fire. Alter the initial assault was broken, the enemy simply backed off and using the positions he had already prepared, attempted to destroy the key bunkers by recoilless rifle and B-40 fire. Simultaneously they moved into Khe Sanh village and setup mortars with which they attempted to shell the compound. At this time the police station was still communicating with the District Headquarters and made it possible to put effective fire on the enemy moving into the village. For the next four hours there were constant attacks or probes against the compound which were beaten off by the valiant efforts of Bru (Montagnard) PFs and the Vietnamese RFs working with the Marines who SGT John Balanco moved to critical areas of the fight, as needed. These various types of soldiers fought as a coordinated team. The four advisors were constantly moving through the compound, reassuring, reorganizing and helping the compounds’ defenders.

At about 1130 the fog burned off. During the next five hours there were three attempts to resupply the beleaguered garrison, which was in dire straits for ammunition. The third attempt included a 46 man RF reaction force that was badly mauled. LTC Joe Seymoe, the Deputy Senior Province Advisor, lost his life in this effort. All during the afternoon CPT Ward Britt, an Air Force FAC, working out of Quang Tri put in numerous air strikes on the massed NVA who were trying to reorganize. On one of these airstrikes he put in two fighters on 100 NVA in the open and after it was over he could not see any movement, just bodies.

The night of 21 January the NVA were unable to make an attack and only sniped throughout the night.

The next morning the evacuation of District Headquarters was ordered after Colonel Lownds, CO, 26th Marine Regiment,ordered the evacuation of the Marines from the garrison. The marines and the wounded were evacuated by air. CPT Clarke and SFC King, two of the advisors, accompanied the District Forces who, using an unknown route, successfully escaped from the District Headquarters.

The Battle of Khe Sanh Village is Over

The morning of 22 January 1968 dawned bright and quiet. The North Vietnamese Army (NVA) forces were gone. There was a sense of exhilaration in the District Headquarters—the attack had been stopped!

Patrols were launched to determine the damage and collect information on the enemy. There were numerous blood trails and bodies found. Over 150 weapons and 3 Rocket Propelled Grenade Launcher 7s (the first seen in South Vietnam) were recovered. Many of the weapons still had cosmoline (a substance obtained from petroleum that is similar to petroleum jelly that is applied to machinery, especially vehicles or weapons, in order to prevent rust on them while in shipment or storage) as they must have just been issued.

As the Marines and District Forces were conducting their limited patrols LT Stamper (Combined Action Company Commander) was boarding and flying by helicopter to the Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB). He was not to be seen again. He radioed back to the Marines to pack their stuff as they were being evacuated.

Colonel Lownds (KSCB commander) sent a radio message to the Advisory team that he could no longer provide artillery support to the District forces. Both CPTs Nhi and Clarke reported this to their superiors in Quang Tri. Bob Brewer, the Province Senior Advisor, said that there was a long meeting. No one wanted to evacuate the District Headquarters as it would be the first governmental headquarters ever surrendered. In the end the order was given to evacuate.

All of the Marines, SFC Perry, with all of the wounded, LT Taronji, his assistant and SFC Kaspar were evacuated by helicopter. SFC King and CPT Clarke worked with CPT Nhi to organize the withdrawal from the village. The small force of about 140 men followed a little-known trail to reach KSCB. Throughout the trek CPT Clarke was coordinating with the Special Forces in FOB-3 for mortar coverage along the route and a reception when they got to KSCB. (The Marines had told the advisors that armed Vietnamese and montagnard soldiers could not enter their compound.)

The small force reached FOB-3 and were assigned defensive areas on the it’s perimeter to prepare fighting positions. Little did they know that this was going to be home for over 77 days.

CPT Clarke reported all of the weapons that had been captured and left behind in the rush to evacuate. The Special Forces quickly organized a raid to get back into the District Headquarters to recover the NVA weapons and destroy anything else of worth that was there. CPT Clarke was the second in command of this raid and led the Special Forces into the compound after they were landed in the wrong spot (in at least 10 year old French mine field).

The weapons were loaded and hauled off. The warehouse full of bulgur wheat and vegetable oil was rigged for destruction. After evacuating the weapons, the helicopters returned for the raiding force. As they were leaving, CPT Clarke remembers lying on the floor of the last UH-1 helicopter out and emptying his 30-round magazine at an NVA patrol that was approaching the village from the west.

Later the charges set in the food warehouse exploded as did the grenades that CPT Clarke had used to booby trap the food in the Advisor’s store room.

The battle of Khe Sanh village had ended. Just over 55 years ago, but sometimes it seems like yesterday.

Post Scripts: The Special Forces at Land Vei offered what was called a Mike Force to re-secure the village, but this request was never acted upon. When the 37th Army of Vietnam Ranger Battalion was sent to Khe Sanh the original intent was for it to be used to re-secure the village, but the Marines would not support such an attack.

General Westmoreland’s grand plan was to draw the NVA into a fixed, firepower intensive battle. The village of Khe Sanh, its inhabitants and defenders were expendable in this grand strategy. The political loss of a seat of government was of little consequence to the attrition strategists.

Air Support for Khe Sanh village

In the last several articles we have discussed the bravery of the defenders on the ground in Khe Sanh village. In this article we shall discuss the use of air support to provide a critical ingredient in the successful defense of the District Headquarters and the rendering combat ineffective of a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regiment.

The dense fog of January 21 finally burned off in late morning. A Marine Forward Air Controller (FAC) put in a flight of 2 F-4s to attack targets to the south of the District Headquarters. One of the F-4s was shot down. Following this the FAC advised that: “That’s all I can do!”

Fortunately, part of the preparations of the defense of the District Headquarters was to establish an alternate form of communication with the Province Advisory Team in Quang Tri. Radio contact with Quang Tri was always spotty at best, in spite of numerous efforts at antennae construction and acquisition of more powerful radios. The Special Forces had established a radio relay site on a high hill north (hill 950) of the Khe Sanh Combat Base. The Special Forces were able to talk to Quang Tri and thus relay messages. CPT Clarke kept Quang Tri informed as to the status of the defense and when the Marine FAC could not provide additional air support he requested it from Quang Tri.

CPT Ward Britt (one of the advisory team’s FACs) flew his light observation aircraft through the valleys under the low clouds and fog to reach Khe Sanh and to coordinate for air support. He requested air support from air craft attacking targets along the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos. The pilots flew below through the clouds to the village. Every time he coordinated for bombs on a target and he blew away the trees to the south he found more targets.

CPT Nhi was listening to one of the NVA tactical radio nets and heard a request for additional stretcher and bearers to carry off wounded soldiers. This was passed to CPT Britt who found the force of about 100 enemy and after another air strike he could not see any movement. This became the norm as CPT Nhi provided target locations to CPT Clarke who then vectored CPT Britt to the target.

In the middle of this CPT Britt landed at KSCB and refueled under fire. He remained on station until the approach of dusk. At that point he had to return to Quang Tri. For his bravery he was awarded the Silver Star.

CPT Clarke and CPT Nhi tried to guess where the enemy would go to regroup. Based upon their analysis a B-52 strike was requested. They provided a rectangle 3 kilometers long and 1 kilometer wide that was centered on the hilly area about 6-7 kilometers south of the District Headquarters. The Province Advisory team coordinated with the Air Force and the mission was flown. Several days later a NVA soldier deserted and was picked up by the Special Forces at Lang Vei. He told them that his unit had been hit by the B-52 strike.

Before the B-52 strike a gun ship (Spooky—a C-47 plane that carried flares and several mini-guns) patrolled the area and engaged every target that it saw. It was a quiet night except for some snipers.

The combination of artillery, air support and the bravery of the Bru, Vietnamese, Marine and army soldiers inside the headquarters combined to render a regiment combat ineffective

The Village Fight

The Village Fight

Khe Sanh Village with the District Headquarters in the bottom center—west end of the village

On 20 January CPT Nhi, the District Chief, CPT Clarke and SFC King set out on a reconnaissance patrol of the area south west of the District Headquarters. We wet about five kilometers and set up a small patrol base with small teams patrolling in clover leaf patterns around the patrol base. Not much after we had gotten established, CPT Clarke received a radio call from the Special Forces at Lang Vei. He was told that the small force needed to get out of the area immediately. He argued that the whole mission had been coordinated with the Marines at the Khe Sanh Combat Base, but was told in no uncertain terms to move out. He understood the message when it was repeated by CPT Willoughby form the Lang Vei Special Forces Camp—a voice that he recognized. After recalling our patrols the small force returned to the District Headquarters without incident. An hour later a B-52 bombing mission could be heard coming from the general area where they had been.[i]

That evening CPT Clarke took a hot shower, not realizing that it was the last one that he was going to get for several months.

At 0500 on the morning of 21 January 1968 the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) attacked the Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB) with rockets and artillery. The sound of the barrage woke up the District Advisory Team and the defenders of the District Headquarters (a mixture of Bru Montagnards, Vietnamese Regional Forces, Marines from Combined Action Company O (CAC-O) and the small 4-man advisory team.

At 0530 the ground attack against the District Headquarters began. NVA after action reports suggest that the attack was 30 minutes late in being launched. The attacking force from the 66th NVA Regiment had been slowed down by the B-52 strike of the previous day—all of the downed trees etc. that it caused.

The weather on the morning of 21 January 1968 was extremely foggy with visibility down to no more than 5-10 yards. Fortunately, some of the improvements made due to the observed activity at the KSCB included the emplacement of trip flares along the entire outer perimeter.

Another improvement that CPT Nhi had made was to place a 3-man element on the roof of the warehouse. These brave Montagnards were equipped with a case of grenades to drop on any one trying to conceal themselves behind the warehouse. Both of these improvements were to prove critical to the defense of the District Headquarters.

The District Headquarters to include the Regional Force Compound

to the south bordering the Landing Zone

Note the red arrow indicating the critical seam between the two parts of the District Headquarters defense

The attack included artillery and mortar rounds impacting throughout the area. One bunker was directly hit and collapsed on the occupants. SFC Perry dug the survivors out and treated them in a makeshift aid station. The enemy sought to penetrate the compound in the seam between the Regional Force Compound and the District Headquarters which was defended by Bru Montagnards and Marines under the command of SGT John Balanco.

The initial ground assault was announced by trip flares being set off. The Bru knew where to shoot when certain trip flares were set off. Thus, they could engage the enemy that they could not see. The same was true for Regional Force (RFs) in their old French fort made of pierced steel planking with about 12-18 inches of Khe Sanh red clay filling the space in between. It stood up well to the enemy attack. The Khe Sanh red clay was like concrete.

CPTs Nhi and Clarke were in the command bunker in the center of the compound. CPT Clarke was to request and adjust over 1100 rounds of artillery during the next 30 hours. The advisory team had 4 pre-planned concentrations that were shaped like an L and located basically at each corner of the compound. By moving those concentrations East and West and North and South one could cover the whole compound with steel. The only rounds fired were fuse variable time (VT) a round that detonates in the air and throw shrapnel down to hit everyone who was not in a bunker with over- head cover.

CPT Clarke never claimed it, but it was reported that he adjusted the artillery so that it landed on the defensive wire and above the bunkers that were defending that wire. This artillery fire is documented in the book Expendable Warriors. (He did in fact call artillery fire on the compound and has subsequently admitted it.)

The trail just outside the compound that ran behind the pagoda was like the bocage area of Normandy where the travel had created a wall and subsequent trench. It was in here that the NVA staged for their attack and where the artillery pre-planned fires were able to inflict significant casualties.

The Marines in the compound became the fire brigade. SGT Balanco, after conferring with CPT Clarke, moved Marines around to meet the largest threats. The presence of Marines bolstered the morale of the RFs in the back compound who who had borne the brunt of the attack. The ground attacks came in several waves, each of which was stopped. The key threat was at the area against the bunkers on each side of the seam between the two parts of the headquarters.

The NVA seemed to be on something. As an example, when CPT Clarke shot with a grenade round an NVA sapper, who was trying to take out the north western bunker in the RF compound the two parts of his body, though separated continued to move towards the bunker with his pole charge. (A charge on the end of a pole to place the charge into an aperture of the bunker and detonate it so as to create a gap in the defense.) SFC Perry also thought that the NVA were on something.

In the late morning the fog burned off and the defenders were able to get some air support. This will be the discussion in our next article.

[i]CPT Clarke later learned that the mission was aimed at a North Vietnamese Army Regiment in that area. They were lucky that they did not “find” them as the small District force would not have stood much of a chance against that sized force.

Was America Duped at Khe Sanh?

Khe Sanh remains an item of historical interest. Articles continue to be written about the battle. With the 55th anniversary of the siege of the Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB) we may anticipate a plethora of articles about the battle that decided the Vietnam War. Two years ago there was an important such article in the New York Times (“Was America Duped at Khe Sanh?”). The article by John Mason Glen is spectacular in its attention grabbing title but weak on strategic analysis. Having lived through the battle and written about it in Expendable Warriors: the battle of Khe Sanh and the Vietnam War, I feel uniquely qualified to rebut Glen’s argument.

The main theme of the article is that the attack on Khe Sanh was a diversion to draw American forces away from the populated areas in anticipation of the Tet Offensive which started 9 days after the beginning of the siege of the KSCB. This argument is inaccurate for many different reasons:

- The attack on Khe Sanh had been anticipated for 3 months. Elements of 2 Army Divisions had been moved north in vicinity of Hue and Quang Tri. It was these forces that blunted part of the attacks on those two province headquarters during Tet 1968.

- Khe Sanh was reinforced by 4 battalions of Marines with most of the reinforcements arriving after the North Vietnamese Army launched its missile and artillery barrage on 21 January 1968. (More on the multiple implications of this attack in subsequent articles.) 4 battalions of Marines in the bigger scheme of things was not consequential to stopping the Tet attacks.

- The diversion of air assets to support the defense of Khe Sanh was not as significant as Glen would have one believe. Much of the air support used was B-52 carpet bombing not pin point close air support. Such bombing approaches were inappropriate for populated areas.

- Glen mentions the internal opinion divisions within the North Vietnamese leadership. One faction was focused on the Tet offensive and the other on Khe Sanh. He correctly points out that one faction focused on the general uprising goal while General Giap was seeking to break the American public support for the war by the attack on Khe Sanh. He wanted to repeat his success at Dien Bien Phu where the French public support for the Indochinese war was destroyed. To people like Glen it was one or the other. Why couldn’t they have been reinforcing? Glen does not examine this point.

- The agony of Khe Sanh played out for 77 days on the screens and in the newspapers of main street America. This is where the war was lost! Certainly, Tet contributed to the loss but it was Khe Sanh that was the deciding factor.

- It should be noted that in the Burns PBS documentary which has been critiqued on these pages the siege of the KSCB is barely mentioned—another of its fatal flaws as has been recounted on these pages.

- In fact, both Khe Sanh and Tet were significant failures militarily for the North Vietnamese. They lost both battles. The war was there to be won, but the political will to do so had been lost. Giap had been right. (There is a unique event highlighted in my book that makes this point explicitly.)

But the bottom line is that the battle of Khe Sanh was won and the war lost at the same time.

In my next response to the Glen’s article I will respond to his critique of General Westmoreland. Stay tuned!